An article is basically an adjective. Like adjectives, articles modify nouns. In English, there are two articles: the and a/an.

- The is used to refer to specific or particular nouns

- a/an is used to modify non-specific or non-particular nouns.

The is a definite article and a/an is an indefinite article.

In Afrikaans we use “die” and “‘n”

Bestimmte artikel / Definite article

In English we use “the” and in Afrikaans we use “die”

| Kasus (Case) | Maskulinum (der) | Femininum (die) | Neutrum (das) | Plural |

| Nominativ | der | die | das | die |

| Akkusativ | den | die | das | die |

| Dativ | dem | der | dem | den |

| Genitiv | Des (-s, -es) | der | des(-s, -es) | der |

In Genitiv, the Nomen gets an s or es at the end for Maskulinum and Neutrum e.g. Der Hund des Mannes

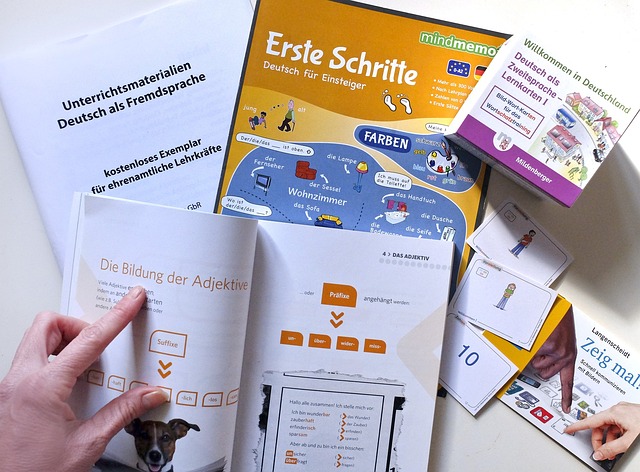

Gender

It would be best if you learned the gender of each new word (Noun) you learn in German. This is not always easy to do and we hope the list below will be of some help. These lists give an indication of which article to use for some words e.g all Months are masculine (der) and most words ending in “e” are feminine (die).

Unbestimte artikel/ Indefinite article

English – a(n)

In German, the word “a” is “ein”.

The ending will change depending on gender and also on the case of the sentence

Also applies to Mein, Dein, Sein, Kein

| Kasus (Case) | Maskulinum (der) | Femininum (die) | Neutrum (das) |

| Nominativ | ein | eine | ein |

| Akkusativ | einen | eine | ein |

| Dativ | einem | einer | einem |

| Genitiv | eines | einer | eines |

Related content

Verbs

Verbs are action words (e.g., to run, to eat, to learn).In German, verbs that describe actions are known as “tun-Verben” (doing verbs) and verbs that

German Grammar – Cases/Kasus

Präpositionen

German Grammar and Language

Here are some links to German Grammar information.It is a compilation of information I gathered over time. I hope you find it useful. Please notify

You must be logged in to post a comment.